|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check out our web directory of the UK

roofing and cladding industry

www.roofinfo.co.uk |

Sign up for our monthly news letter. |

|

|

|

|

Curves of any kind on a roof soften the look

and make it look either very modern, or very old. But achieving a curve

in the length of the rafter at the eaves using what are, in general

principle, flat and square slabs of clay, slate or concrete is far from

ideal, but possible.

This first part looks at the background and causes of

sprockets and how they should be approached.

There are certain compromises and facts of life

that need to be understood and worked within to achieve a sprocket at an

eaves; but first we need to define what it is we are talking about. A

sprocket eaves detail is formed when the lower courses of tiles or

slates lay at a shallower true pitch than the tiles or slates in the

courses above. Why does this happen, or why would anybody want to form

this detail?

History

The origins can probably be traced back to cruck-framed houses where

columns were bent over to form the roof structure onto which were fixed

purlins and common rafters. The floor joists were extended out to beyond

the wall face and an additional purlin connected between ends of the

floor joists. This meant that the eaves course of tiles or slates were

often laid at a shallower angle, but as the main rafter pitch was very

steep and the roof was covered with thatch it was not an issue.

Between 1900 and 1930 it became popular with the

arts and crafts movement to introduce features into houses that harked

back to old styles of housing using natural materials, like brick,

stone, plain tile, or stone slate. This was fine for rich people who

could afford such flights of fancy, but the architects and planners

picked up some of the design features and insisted that these were

perpetuated to try and maintain the look of a bygone era. Unfortunately

the construction of a modern house is very different to the traditional

cruck-framed house with a thatched roof covering, and therefore not

always appropriate for a sprocket.

Construction

Today the most common reasons for forming a sprocket are:

-Using a depth of fascia board that is too deep; the carpenter sets the

soffit to just miss the head of the upper floor windows, installs the

fascia board from that point and does not cut down the top edge of the

fascia board.

-An over fascia ventilation grill has been specified and no allowance

has been made with the height of the fascia board, so once the grill is

installed the overall height is too high.

-The architect specifies a very deep soffit to give the building a

Mediterranean look, but does not correspondingly lift the roof to allow

the rafters to be extended at the same rafter pitch. By going

horizontally outwards and not correspondingly upwards the extended

rafter has to be at a shallower angle. In the past the reasons may have

been to make the rafter length an exact module of the tile or slate

gauge, to prevent the need for cutting tiles at the ridge course.

The roof covering will always follow the

line of the rafter, but form a curve made up of facets between the

fascia board and the main rafter pitch; sometimes in one sweep and

sometimes in two sweeps, depending upon the extension rafter. It is

therefore almost impossible to hide a sprocket if it is formed within

the roof structure. Some specifiers firmly believe (because they have

been told by their peers) that it is good practice to form a sprocket at

the eaves, because it slows the rainwater down as it comes off the roof

and into the gutter. Whilst it is true that water running off a shallow

rafter pitch will flow at a slower speed than from a steep pitch; where

|

|

|

the water flowing down a steep rafter pitch

meets a sprocket, the water goes into ski jump mode and keeps travelling

at the same speed. However, it now has a new direction of travel and

will overshoot the gutter during heavy rainstorms.

Sprocket curve

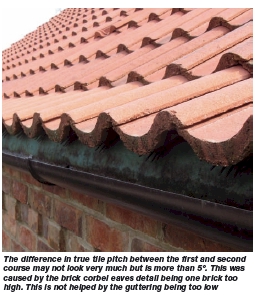

Depending upon the thickness of the tile or slate, and the gauge at

which they are set, this will determine the amount by which the sprocket

will diminish; the ratio is in the region of 1:8. This means that under

most circumstances if the true pitch difference between the first course

and the second course is 16º, the true pitch difference between the

second and third course will be 2º and between the third and fourth

course will be 0.25º. Therefore under most circumstances a sprocket will

extend over about three or four courses before it becomes too small to

measure. The relationship between tiles on adjacent courses is very

important and therefore introducing a true pitch difference of, say, 10º

can be very detrimental.

Regardless of which roof covering is to be used on the

roof, the true pitch of the eaves course must not fall below the minimum

recommended for that roof covering. Because tiles and slates lay at a

shallower angle than the rafter that they are fixed to as they lap onto

a tile or slate below, allowance has to be made as all recommendations

are quoted as rafter pitch not true tile/slate pitch. With plain tiles,

depending upon their thickness and camber, the true tile pitch will be

between 9 and 10º less than the rafter pitch. For most interlocking

tiles the true tile pitch will be between 4.5 and 6º less, and for

double lap slates will be between 3 and 4º less. Therefore the minimum

true tile/slate pitch for the eaves course is the minimum rafter pitch

less the tile to rafter pitch. For instance a flat interlocking concrete

tile with a minimum rafter pitch of 17.5º will have a true tile pitch of

13º and a plain tile will have a minimum true tile pitch of 26º.

Conclusion

Sprockets at the eaves are visually pleasing to create that old

traditional look, but can also cause problems when they are constructed

for decorative purposes only. The steeper the rafter pitch, the easier

it is to get water into the gutters at the eaves.

Tips

- Never lay the eaves course of tiles

or slates below the recommended minimum true pitch.

- When re-roofing where there is a

sprocket, always use the same type of roof covering as used

previously, as it will have been chosen wisely.

- Avoid where possible a sprocket

formed on a new roof

|

| Compiled

by Chris Thomas, The Tiled Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove,

Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey, RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774 |

|