|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Check out our web directory of the UK

roofing and cladding industry

www.roofinfo.co.uk |

Sign up for our monthly news letter. |

|

|

|

Slating and tiling battens have

developed from the thin coppice saplings that were used to support and

fix the reeds in thatching. For early peg tiling the timber was split

with an axe or lathing hammer to give it a square top edge for the oak

pegs to rest on. Being split, the battens were never straight, so were

kept as narrow as possible to allow the tiler to bend them and achieve

the straightest line possible when nailing them to the rafters.

The rafters were often a quarter of a tree trunk,

and tapered from eaves to ridge, so the spacing of the rafters were at

close centres of 300mm-400mm. The size of the batten was, therefore,

sometimes as small as 25mm x 12mm.

With the introduction of mechanised saws it

became possible to cut rafters to a regular size, allowing the rafter

centres to increase. The offcuts were sawn down to make the battens;

this practice is still used today. With split timbers it was essential

to have the longest knotfree length you could achieve, as the grain was

impossible to keep straight, close to a knot.

With sawn timbers, knots have become more common

in battens. With the introduction of trussed rafters, the rafter spacing

has expanded out to 600mm, requiring battens to be larger to span

between the rafters at wider centres.

Timber

Because timber is a natural

material that comes from many species of coniferous trees, the

characteristics of the material will be different. This will have an

effect on the splitting and bending properties of the finished batten.

To reflect this, battens should be sourced from

either European and home-grown Redwoods, Whitewoods, Sitka Spruce, Scots

Pine, Canadian Spruce Pine and Fir, Douglas Fir- Larch and Hemfir.

Timbers that do not fit into these classifications should not be used

for battens.

Prior to the introduction of European competition

rules, timber for battens came from different climatic zones, and the

density and spacing of the growth rings could vary. Generally, timber

that grows quickly in a warm wet climate will have wider and softer

growth rings than timber grown in a cold dry climate.

The spacing and density of the growth rings

affects the grip of the timber to a nail fixing.; the harder it is to

drive a nail into timber, the harder it will be to pull it out.

British Standards

There is no specific British

Standard for timber slating or tiling battens, but there is a definitive

list of species and permissible characteristics that all battens for

slating and tiling should comply with, contained in BS5523: The code of

practice for slating and tiling: 2003, which contains a table of minimum

batten sizes for the common roof coverings of natural and FC slate, and

single and double-lap clay and concrete tiles. For rafter centres up to

450mm centres, all tile roof coverings and FC slate should use 38mm x

25mm battens, while natural slates should use 50mm x 25mm. For rafter

centres up to 600mm centres, 50mm x 25mm battens should be used for

natural and FC slate, and interlocking clay and concrete tiles. Plain

tiles should use 38mm x 25mm battens.

It may be possible by calculation to prove that for a

specific situation, 38mm x 19mm battens are appropriate, but without

valid calculations the recommendation contained in the table should be

used. For rafter centres in excess of 600mm the batten size needs to be

calculated. There is also a maximum and minimum tolerance: +/- 3mm wide,

+3mm deep.

The main reason for using 50mm x 25mm battens, particularly with natural

slates, is to reduce the amount of batten bounce at midspan when driving

in nail fixings. |

|

There comes a point, with small

sections of timber, where the force required to push the nail into the

timber is more than the force to bend the timber. Therefore, the batten

bends before the nail goes into the batten. With head-nailed tiles it is

possible to hold the batten while you nail, to stop the batten bending.

But with centre-nailed slates this is almost impossible.

The reason why all the battens are 25mm deep,

regardless of the rafter centres, is to ensure the maximum nail-grip for

the nails specified for the tiles or slates. With a 19mm-thick batten

there is the risk that the nail will pass through the batten and stick

6mm out of the back of the batten, and may puncture the underlay.

Battens that are 50mm wide should not be used with plain tiles as the

position of the eaves tile relative to the first whole tile is critical.

If a 50mm wide batten was used, the eaves tiles would not align

correctly.Installation

It is always better to use rectangular sections of timber on

the roof as they are less likely to roll if stood on. All battens

generally come treated with preservative. While there are some locations

where it is mandatory (Surrey), it is a wise precaution to use treated

timbers, but will add a slightly higher risk of pollution entering the

environment when the building is demolished. No batten should be less

than 1.2m long, so that at 600mm centres the batten will rest on at

least three rafters. Battens should always be joined on the centre line

of a rafter and with trussed rafters; no more than one in any group of

four consecutive battens should be joined on the same rafter.

For tiles and slates where the batten gauge is less

than 200mm, no more than four in 12 consecutive battens should be joined

on the same rafter. Knots that affect two edges, up to a certain size,

may remain in a batten, but where the knot affects three edges, or is

over a certain size, the knot should be cut out and the batten joined on

a rafter, as knots can severely weaken the performance of a batten and

make fixing nails into, or through it, very difficult. Battens should

always be set out to a calculated gauge which is measured for tiles from

top of batten to top of batten. While slates are laid to the centre of

the batten, the position of the eaves slates should be set out so that

all gauges above that point are to the top edge of the batten.

Rigid sarking

In Scotland it is traditional with natural slates to lay ply or OSB

board directly onto the rafters, and cover with underlay to keep it dry

until the slates can be nailed directly through the underlay into the

boarding. This method allows the roof to be constructed quickly without

knowing what will cover it, as the batten gauge is irrelevant. The lack

of slate battens means that where there are inclined valleys there is no

natural space to form the tilt or the welt of the valley construction,

without kicking up the edge slates.

Tips

- All slate or tile battens should

comply with the recommendations of BS5534, for timber species,

markings and sizes.

- Battens less than 1.2m long should

not be used on a tiled or slated roof, except as a noggin.

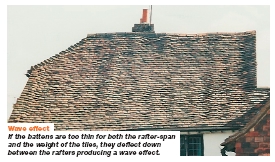

- Undersized battens will sag between

the rafters and appear as a series of waves in the roof covering,

after a few years.

- The same thickness of batten should

be used throughout the roof to ensure the roof covering lays in the

same plane.

|

| Compiled

by Chris Thomas, The Tiled Roofing Consultancy, 2 Ridlands Grove,

Limpsfield Chart, Oxted, Surrey, RH8 0ST, tel 01883 724774

|

|